By Dogu Eroglu – JUN 30 2016

International explosive manufacturers, based in Spain, India, and Australia, establish partnerships, or simply acquire local companies in Turkey, only to re-export their detonating cords to ISIS and other Salafi jihadists that are aligned with Jabhat al Nusra. Meanwhile, Turkey’s fanatically anti-Assad government seemingly turns a blind eye to the shipment of IED materials, and allegedly orchestrates it according to a local court’s bill of indictment, through former military and police personnel.

Since ISIS’s siege of Kobane failed ultimately, the detonating cords left behind on the battlefield, which had been used in the manufacture of IEDs (Improvised explosive devices), keep revealing what has been happening in the hinterlands of war, especially in Turkey. Tracing the Supply of Components Used in Islamic State IEDs, the report prepared by CAR (Conflict Armament Research), joined together with findings from Turkey, and ongoing trials in local courts, exposes the most parts of the production and supply chains, that ends in the hands of Salafi jihadists struggling to keep their fight in Syria and Iraq afloat. Deeper scrutiny of exchanges of detonating cords provides the essentials of the scheme that stretches over countries: International explosive producers export the detonating cords manufactured either by themselves or their sub-branches in Turkey or other neighboring countries of Syria; importer domestic firms –partly or wholly owned by international manufacturers–sell batches of detonating cords to domestic buyers; eventually, the detonating cords are captured by YPG forces following the push-back of the ISIS siege. The serial numbers engraved on the batches found in the outskirts of Kobane exposes the dates of production, and every stage of the journey of detonating cords. In 3 instances, later it turned out that detonating cords were smuggled to ISIS, after licensed dealers sold the explosives to third parties in Turkey. AKP government announced new measures to restrict the purchases of fertilizers that contain ammonium nitrate and gas cylinders, on the grounds that those materials are used for manufacturing of IEDs, following the vehicle borne IED suicide attack –allegedly perpetrated by TAK, a PKK-offshoot Kurdish armed group– in Istanbul that killed 11 people. Yet, the same government is either orchestrating or turning a blind eye to the trafficking of detonating cords, another IED component. According to a court case, all along this smuggling operation of detonating cords might have been conducted by state officials, or at least a combination of current and former members of security apparatuses, for the government to be exempted from accusations on their alleged support to Salafi jihadists.

In modern warfare, IEDs are one of the most essential tools violent non-state actors turn to narrow the military capability gap between them and sophisticatedly armed state military apparatuses. No matter how lethal, a typical IED is simple to assemble; its materials are easily procured, as all components are commercial products labeled neither weapons grade materials nor dangerous goods; and its deployment methods do not require advanced training. The crudeness of IEDs’ manufacture and employment methods makes it the best element of an insurgency’s arsenal. Due to the nature of the IED, its components could be obtained from any market without trouble, whether conflict-driven or not, the supply chains for IED components reach anywhere on the planet without being harassed by the international sanctions against or embargoes of arms and ammunition trade.

Despite IED components undergo a series of changes based on the preferred agent of attack, and materials available, most systems have common features. The switch or the activator to initiate the detonation; the battery; the fuse –usually detonating cords– that transmits system’s energy to explosives; the charge, the actual material that explodes in other words; and the container that holds explosive material are the essentials of IED.

The nature of IEDs –a lethal device, usually comprised of non-lethal components– makes it a flexible tool; a particular ISIS cell, or a part of the ISIS war machine that is cut-off from its once reliable supply routes, may still produce effective IEDs, by substituting its components with inferior –not necessarily– ones. If access to plastic explosives such as TATP, triacetone triperoxide, that is used during November 2015 Paris attacks is limited, then the IEDs use the combination of aluminum paste and fertilizers that contain ammonium nitrate (both non-lethal and commercially sold materials) as the main explosive in the IED system; unexploded shells might come handy as well whilst trapped on the battlefield. More to that, the methods of execution of IEDs are limitless too; once rigged, IED could be delivered to the target by any vehicle, including cars, trucks, boats, and motorcycles. One of the most common ways to deliver an IED is detonating the device remotely, after planting it to a roadside or any other location. In some cases, IEDs have been even strapped to animals.

It is not ISIS that introduced this simple but lethal instrument to the battlefield. The first instances IEDs appeared in the theatre of war were during the WWI, yet it took several decades until the IED became a full-fledged weapon of its own. The struggle against crude yet effective IEDs goes back to Afghanistan. Taliban employed IEDs to overbalance Western forces’ technological superiority, causing at least 2,453 fatalities between dates January 4 2004 and December 31 2009, excluding the perpetrators killed during the attacks. According to the dataset extracted from leaked US defense cables, there have been 7,527 individual IED attacks in the same period.

The invasion of Iraq was no picnic as well; the Iraqi insurgents proved this simple weapon could be one of the most effective tools against their Western adversaries. The effectiveness not only came from its simplicity, but also from its obscurity. Many times attackers with IEDs managed to pass through security checks and control points, outwitting electronic counter measures to detect explosive devices. IED attacks claimed at least 1,832 lives from the ranks of US forces in Iraq, since the beginning of the invasion; constituting 40,8 percent of American casualties. ISIS continues that tradition.

Unlike Afghanistan and Iraq, Western coalition does not operate on the ground during the military campaign against ISIS, except for minor instances, thus similar up-to-date data is not available yet. But figures compiled by ISIS itself show IEDs are given great importance for the organizations’ strategy that prioritizes frequency over impact, when it comes to attacks. ISIS’s own data shows IEDs are indeed the weapon of choice. al-Naba published by ISIS’s main media arm al-I’tisaam Media Foundation on March 31 2014 that covers all the attacks perpetrated by ISIS within the period of November 2012 to November 2013, reveals that IEDs were used in almost one out of every two attacks. Out of 9,540 different operations undertaken, with 4,465 individual events, IED attacks were accounted as the most conventional method by a far margin (This figure does not include vehicle-borne or motorcycle-borne IED attacks, and attacks through suicide vests).

Thanks to Turkey’s loose border controls policy, country’s security apparatus’ indifference to the logistic operations of Salafi jihadists, and government’s unwillingness to cut lifelines of ISIS and Jabhat al-Nusra affiliates, one of the key components of IEDs, the detonating cords, are highly available to ISIS and other jihadist organizations now. Following CAR’s report that documented the detonating cords used by ISIS have in fact been transferred via Turkey, other evidence from failed shipments of explosive materials that made its way to public eye sealed Turkey’s indispensable position within the global supply chain of detonating cords.

Detonating cords stopped at Turkey’s Syria border

The first instance that put an international detonating cord manufacturer’s name side by side with Salafi jihadists operating in Syria came in last year. On June 10 2015, officers in Hatay Cilvegozu Border Control, the gateway of Jabhat al-Nusra affiliated groups into Syria, notified Ankara on a suspicious cargo, which seemed to have acquired all the necessary paperwork for exporting dozens of batches of detonating cords, a material widely used in mining and construction sectors other than being the key element of IEDs, to Jordan via land route passing through Syria in conflict. As soon as the controversy received press attention, border administration couldn’t help but to halt the truck’s passage, apprehend the driver, and seize the cargo, a million meters of detonating cords, an ample amount of explosives. 210,000 dollar worth cargo weighing 24 tons was meant to be delivered to a firm based in Amman, Jordan, ASR Trading Company, yet it never left Turkey. The explosives that got stuck in Cilvegozu Border, belonged to Maxam Anadolu, a subsidiary of Spanish explosives and ammunition giant Maxam International, a multi-sectoral corporation with a military arm Expal, which is one of the largest defense contractors in Europe.

Allegedly en route to Jordan

Having all the necessary documentation from related ministries, Maxam Anadolu sent the truck filled with detonating cords to Cilvegozu Border Crossing. Nevertheless the question remained; who could have been the recipient of the cargo? Cilvegozu opens in Syria through Bab al-Hawa Border Crossing to the other side of the soil, a checkpoint that is under control of Salafi jihadists for almost 4 years now. Captured by the FSA (Free Syrian Army) on June 19 2012, following the paradigm shift of the Syrian Opposition, Bab al-Hawa has been governed by Salafi organizations Jabhat al-Nusra or an affiliate of it, the Islamic Front.

If everything had gone according to the plan, following its arrival to Cilvegozu Border Crossing on June 10 to 12 2015, the truck loaded with detonating cords would have proceeded to Bab al-Hawa. By that time, however, Jabhat al-Nusra had already passed the control of the border to others. Influential groups of that day, Jabhat al-Islamiya, Nour al-Din al-Zenki Brigade, Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar, and Asala wa-al-Tanmiya had supervision over Bab al-Hawa from time to time since 2014, and they all were aligned with Jabhat al-Nusra, if not operated directly under its sovereignty.

Before the Syrian Civil War had begun, the cargo could have reached Amman, Jordan, by following a 530-kilometer long journey, passing through Idlib, Hama, Homs, and Damascus on M5 highway. Nevertheless, Salafi jihadist control over Idlib and Bab al-Hawa was as tight as now back then on June 2015. Even if the truck had entered that territory without hassle, it had to travel 60 kilometers to the southwest, in order to reach the nearest al-Assad regime held area, Muhanbal district of Idlib. And whilst engaged with countless opposition factions, why on earth would regime allow a truckload of explosives destined to an unknown recipient pass through? Thus, the preference to send the shipment via land route passing through the midst of world’s probably most multifaceted ongoing conflict makes it a long shot to naively contemplate that the cargo was actually going to Jordan.

A front or not: ASR Trading Company

Trying to find out whether a third party called ASR Trading Company truly exists or not, turned out to be a hopeless case after all. The same labor was first attempted by Cumhuriyet Daily reporters Aykut Kucukkaya and Akın Bodur, who wrote the first article on Maxam Anadolu’s halted shipment, only to be followed by Quique Masoni and David Meseguer of Vice España, who covered the same story a year later from a perspective focused on Maxam International’s questionable affairs. Though philosophically speaking, proving something’s nonexistence is much harder than coming up with evidence that suggests it exists, I too looked for ASR Trading Company, the company both journalist crews from Turkey and Spain searched for, and left empty handed.

According to two of the service providers that act as business registration agencies, Companies Control Department of Jordan, and Jordan Ministry of Industry and Trade, neither ASR Trading Company nor a company named after direct Arabic translation of the alleged name, ASR Trading Company, exist. The address stated on the Maxam Anadolu sales invoice is nonexistent either; ‘Center Business Algebria Street 19 Flat 312 Block Amman,’ is a dead end, but Algeria Street does exist, and that little street with 7 buildings on it resides on the outskirts of the city’s main business district. Judging from street photos and maps, the address belongs to a residential building. Despite there is no company officially registered in Jordan under the name of ASR Trading Company, ASR Shipping and Trade Company exist, and its profile seems to make the company eligible for being the recipient, or the courier of the cargo. As stated in its introductory texts, the company founded in 2007 handles shipments of cargos to more than 170 countries and excelled in freight forwarding, and specialized in dangerous and oversized cargo. Once hired, company assumes responsibility of nearly all steps of an import/export operation; receives the cargo from the seller, handles necessary documentation for export regime, clears the cargo from customs, and forwards it to the desired third party. Nevertheless, despite that company profile meets the requirements of the shipment operation, the person that answers ASR Shipping and Trade Company’s landline refuses to speak about its relation to Maxam, telling that they have nothing to do with any of names or events I mentioned.

Considering the company profile, it wouldn’t make sense to assume a freight-forwarding firm being the end user of detonating cords, an equipment employed in construction and mining sectors, other than being a vital component of IEDs. Thus, it is only logical to consider that ASR Shipping and Trade Company is either a front, had been come to terms with only to appear on paperwork to make it look cool, or the company was hired to do what it does the best, being an intermediary between Maxam Anadolu and Salafi jihadists in Syria, avoiding any direct links between those two parties. The most convenient route for the shipment would be, for sure, through the sea; after the cargo was brought from Maxam Anadolu’s factory located in Malatya (several hundred kilometers southwest from Mediterranean) to Iskenderun port, it could have been easily sent to Haifa, Israel by a ship, and then the rest of the travel could have been maintained by a truck once more, to cover the distance between Haifa and Amman. A Maxam International spokesperson tells Vice España, Maxam Anadolu had acted in accordance with the laws, and sold a party who has imports permit for explosives. A phone call I receive from the owner of Maxam Anadolu on March 2016 claims the same. Following one of my reports on the supply chain of detonating cords, he tries to clear the air anxiously: “Those people had every necessary permit when they approached us. Why would I risk all my investment for trafficking such small amount of explosives? I invested 8 million Euros in this facility, and went great lengths to establish a partnership with an international manufacturer. Why would I put all those into risk for 200,000 dollars?” Somehow, he suspects those words fall short of convincing me, “We were deceived!” he adds. He refuses to make a clarification on who approached Maxam Anadolu to buy the detonating cords at the first place.

Few months after that conversation, the mystery grew larger, as I find the opportunity of speaking to CEOs and officers of other leading explosives producers and importers of Turkey. Without knowing the conversation I had with the owner of Maxam Anadolu, representatives of other companies gave voice to matching stories. According to that claim coming from competing parties, the same individuals who bought the detonating cords from Maxam Anadolu, had approached other companies too, before concluding a deal with Malatya-based company. “Though the proposed deal looked suspicious –especially the intended transportation through land route– they already had necessary documentation, but we decided not to agree upon terms,” told the representatives of a company, and other accounts were almost identical to that. Nonetheless, a recent rumor they share points to another group of Turkish middlemen paying frequent visits to explosives producers these days. Offering sums way exceeding market values of detonating cords, this time they seek deals to ship explosives to conflict-ridden Libya. “They sent us some sort of import license, obtained from government of Libya. Yet, ‘Which government?’ some would ask when the fragmented status of Libya is taken into account. We had some conversations with the General Directorate of Security, which in turn forwarded the issue to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Eventually they recommended us not to sell any sort of explosives to those parties. Meanwhile, these individuals took things too far that they were even uttering threats to a colleague from another company, who refused their offer,” one representative from an explosives company discloses. Those alleged requests with Libya origin suggests, reputation of the supply chain of explosives via Turkey, made its way to jihads other than the one happening in Syria, through the grapevine.

Maxam: The first to enter Turkey market

Anadolu Nitro, a Malatya based local explosives producer, started its partnership with Maxam International on 2009. The companies became acquainted with during a commercial coupling session organized by TUSKON (Turkish Confederation of Businessmen and Industrialists); not long before, the partnership grew into an official one, with the establishment of Maxam Anadolu, which since then acted as Maxam International’s sub-branch in Turkey. In 2013, the very first batch of explosives came out of the production line from the factory launched in Malatya by the mutual venture, with a co-investment worth 8 million Euros.

Though Maxam Anadolu’s portfolio is limited to explosives, Maxam International operates on a much larger ground. Expal (Explosivos Alaveses S.A.), a Maxam affiliate that specializes in production of projectiles, shells, and detonators, provides arms and ammunitions to at least 40 countries. Over the years, Expal have made itself a notorious reputation by pledging ammunition deals with parties of controversial conflicts. Expal products, particularly projectiles and landmines, became accessories to atrocities committed by Israel and Turkey, during their prolonging oppression campaigns against respectively Palestinians and Kurds.

Maxam’s suspicious sale to Lebanon

CAR investigators debunked a similar Maxam supply route ending up in Syria via a third country. As ISIS left the outer parts of Kobane following the siege’s failure, several batches of detonating cords found in the temporary IED workshops on February 24 2015[1] had some serial numbers engraved on them[2], leading researchers to Lebanon. According to Lebanese officials, a company called Maybel Co. Sarl had received an import permit on May 13 2014, then that permit was expanded to explosives. Lebanon Ministry of Economy and Trade discloses that, Maybel Co. Sarl obtained permissions for importing 5 million fuses, and 3 million meters of detonating cords.

Lebanese officials underline the company that sold the detonating cords and fuses to Maybel Co. Sarl is indeed Maxam International, and the company itself does not bother to deny this claim either. A Maxam International official, nevertheless, asserts that the trade between two companies should not allow anyone to leap to the conclusion that Maxam International provided the detonating cords to ISIS via Maybel Co. Sarl. As a matter of fact the detonating cords, which had been laid hands on for the last time by Maybel Co. Sarl as far as the legal system concerned, are of Solar Cord-III type, produced by an Indian company, Solar Industries. And hence Maxam International easily refuses the allegation, claiming detonating cords produced by a rival company are not present in their inventory. Additionally, despite Beirut acknowledges that Maxam International and Maybel Co. Sarl had agreed terms on sales of explosives; there is no legal record of commercial activity between Solar Industries and Maybel Co. Sarl, manifesting the explosive deal actually took place.

How did Turkey end up as middleman for the detonating cords of Indian companies?

CAR’s report unveils that the leftover detonating cords on soil surrounding Kobane, documented on February 24 2015, were of Solar Cord-II type (note the difference between Solar Cord-III type cords, which is mentioned in an exchange between Lebanese company Maybel Co. Sarl, and Maxam International), and the last confirmed recipient of those batches of detonating cords was Ilci Patlayici [Ilci Explosives] of Ankara, Turkey. Produced on February 2014 by Solar Industries according to the markings engraved on its case, the detonating cords have been imported by Ilci Explosives. Company officials abstain from commenting on how those detonating cords ended up in the hands of ISIS, but they robustly express that Ilci sells explosive material to customers in Turkey and Balkans, who are licensed by the Ministry of Interior, solely and exclusively.

Ilcı Holding began its business operations as a construction firm. Ilci Insaat [Ilci Construction], founded in 1986, rapidly boomed as they started to grasp public contracts. Ilci’s current portfolio shows that at least 10 dams, 5 highway or railway tunnels and bridges, installments of railroads, huge irrigation infrastructure projects, 5 hospitals, schools, factories and thermal power plant constructions, public administration buildings, military facilities, and one stadium project have been completed so far. On 9 particular projects, Ilci also worked as a sub-contractor of Turkey’s notorious TOKİ, Housing Development Administration. Apart from those projects completed under public contracts, Ilci had distributed its assets to a large investment basket.

Until very recently, one of the sectors Ilci had interests in was the market for explosives. Ilci Explosives had been founded on June 15 2007 with a 1 million TRY capital, and remained in Ilci Holding’s hands until May 2010. Solar Industries’ acquisition of 99 percent of Ilci Explosives’ shares introduced Satyanarayan Nandlal Nuwal and Manish Satyanarayan (Two of large shareholders of Solar Industries) into the board of directors of Ilci Explosives. 2011 witnessed a capital increase from 1 million TRY to 8 million TRY, and transfer of nearly all company shares to Solar Overseas Netherlands B.V., Solar Industries’ subsidiary in the Netherlands. Then the company name officially changed to Solar Patlayici Maddeler A.Ş. [Solar Explosive Materials] on August 2014. Thus, when the company referred as Ilci received the detonating cords, which later to be found on Kobane soil after ISIS had left them on the battleground, had already been sold to the Indian company, and controlled all the way by it, yet the company’s name hadn’t been legally changed to Solar Explosives.

Solar Industries, whose products had been detected in Kobane after they acquired Ilci Explosives, is seen as a massive success story in India. A piece appeared in Times of India lays down the history of the company; how the largest shareholder of Solar Industries, Satyanarayan Nandlal Nuwal (Also a board member of Solar Patlayici Maddeler A.S.), made his way to being the owner of one of the world’s largest industrial explosive producers, after his humble beginnings in 1980s as an independent entrepreneur specialized on explosives. Today, Nuwal managed to secure permission from Indian government, to develop warheads, rockets, and missiles. The first private company to get the green light to produce HMX type military explosives, Solar Industries is expected to grow even larger in decades to come according to all predictions. Company’s 2014-15 Annual Report also underlines their intentions to become a notable player in defense industry numerous times.

Supply chain of explosives from Australia to India

Yet another batch of detonating cord is traceable to its Turkey origins. A batch of DC D-Cord II type detonating cord found on February 24 2015, close by Kobane led CAR researchers once again to Ankara. Data observed on the detonating cord revealed that Nitromak Dyno Nobel, a company based in Ankara, obtained it for the last time, and it was Gulf Oil Corporation produced it on December 31 2012. Nitromak Dyno Nobel officials claim that, not surprisingly, their sales are limited to local customers. And, they add, tracing who gets their hands on to the explosives after an explosive company sells the batches is out of their responsibility, if not that sort of tracing activity is impossible at all.

Formerly known as Nitromak DNX, the Nitromak Dyno Nobel was founded in 1988 as a joint venture with DNX Australia, to produce explosives used in the mining sector. Along the years, the company produced explosives in Artvin-Murgul mining basin, and in TKI’s [Turkish Coal Enterprise, a publicly owned institution] coal site in Soma. On 2008, 50% of company shares were sold to Dyno Nobel, and the sale of the remainder followed on 2010, thus Nitromak DNX took the name of Nitromak Dyno Nobel. Later, another Australian firm, Incitec Pivot Ltd became the sole owner of Nitromak Dyno Nobel, after Incitec Pivot Ltd acquired all assets of Dyno Nobel International. An audit report published on November 9 2015 indicate that, Incitec Pivot Ltd owns not only explosives giant Dyno Nobel, but many other small explosives producers as well. However, the detonating cords Nitromak Dyno Nobel sells in Turkey markets are not produced by either of those companies Incitec Pivot owns. A Hyderabad-India based company, Gulf Oil Corporation Ltd, exports the detonating cords that Nitromak Dyno Nobel sells in domestic markets. And the detonating cords are indeed produced by another Indian company IDL Explosives, a sub-contractor of Gulf Oil Corporation Ltd. A product catalogue of IDL Explosives shows detonating cords that have the identical packaging with the DC D-Cord II batch discovered in Kobane.

Both IDL Explosives and Gulf Oil Corporation Ltd are owned by Hinduja Group, which got its name involved into numerous illicit arms deals. With its over-72,000 employees, and minimum estimated asset value worth 25 billion $, Hinduja Group is becoming one of the leading arms and ammunitions providers to the Indian armed forces, with a bullet. On one of many scandals, it was claimed that 3 of Hinduja Group owners, 3 brothers in fact, had given bribes to Indian politicians and bureaucrats on 1986, in return for Indian armed forces pledging a contract of 400 howitzers, with a Swedish company Bofors.

Emerging patterns

In a nutshell, different supply routes of components that are used in the manufacture of IEDs by Salafi groups in Syria and Iraq show similar patterns. The subsidiaries or affiliates of international explosive producers import the detonating cords from their larger partners[3]. The next step is tricky however; the track on the detonating cords is lost, as soon as the licensed firms in Turkey sell their goods to third parties. Then all of a sudden, the detonating cords appear at the hands of ISIS, at warehouses next to conflict areas. Where is the missing link? What happens during the disappearance of the detonating cords, from their departure out of the last legal party –domestic producers or sellers– to their reemergence at the hands of ISIS?

Nevertheless, scrutinizing the legal sales-records of explosives companies might turn out to be very fruitful for tracking down the movement of explosives. The law in effect in Turkey obliges potential buyers of explosive material to disclose their identity, address, and intent for using the explosives to the governorship of the city, where the explosives sale is taking place. A customer could manage to buy explosives, if only the governorship grants a permit to a particular request, and buyers are unable to receive permanent licenses; each request for buying explosives should be evaluated independently. Articles 118, 119, and 120 of the related directive assert that explosive material cannot be sold to unauthorized buyers, and those explosives are not allowed to be resold by the end users, once acquired. So in that fashion, if Salafis use proxies to obtain explosives from official sellers, all suspects, and every step of exchange should be on the books.

‘Onion truck’: More than meets the eye

When it comes to trafficking turning into a second nature to warfare, an ancient practice appeared more or less the same time with the emergence of the very first communities, some might reiterate the famous saying from the Old Testament, “There is nothing new under the sun. It has all been done before.” Nevertheless, one particular trafficking operation (In our case, trafficking of a sensitive explosive yet civilian material, detonating cords, which is essential to the manufacturing of IEDs) run by a group of alleged military men with the assistance of an explosives company and a hired truck driver, is full of genuine surprises.

Following the publication of CAR’s report, the companies, whose names were mentioned in it as accidental or incidental accessories/suppliers to the trafficking of detonating cords, remained silent, only because CAR’s research had fallen short of providing the missing link. The watchdog organization had managed to document the whole journey of ISIS’s detonating cords found in Kobane, after the demise of the siege, except the way those batches of explosives traveled from inventories of Turkey-based explosives sellers or producers, into Syria. Thus, this allowed the companies to stay relatively distant from direct accusations from the public. A lawsuit at a local court, namely Sanliurfa Assize Court, exposed that missing link; at least it partially shed light on the mystery, providing us one of the trafficking methods to be watchful of. On September 8 2015, local police stationed close by Akcakale, once a favored ISIS spot for border crossings into Syria, interrupted a truck on its way to the town, which had been seemingly carrying onions to the wholesale market hall. A plain search surfaced that the truck was full of detonating cords, and traffickers had attempted to conceal the batches with a trifle amount of onions, which the police couldn’t help but notice.

The simplicity of the deception, or the lack-there-of in the case of the onion truck might be easily misleading. Initially, one might speculate on the poor skill set of the traffickers, but the vulgarity of the camouflage, and the overall negligence suggest that trafficking bunch of explosives to Salafis fighting on the world’s most troubled soil at the moment, had been considered as simple job by them, something like shooting fish in a barrel. It further implies that traffickers were enjoying either a general level of amenity given to pro-Salafi supply of arms and ammunitions or IED components into Syria and Iraq, or the safe passage of that particular shipment were guaranteed by authorities. Considering 6 out of 10 accused Turkish nationals in the court case are suspected to be military personnel (Military and the accused neither deny nor confirm that, assumedly due to the nature of job descriptions of the accused), it is highly probable that the particular shipment was a government-sanctioned operation. On the other side of the coin, government, TSK (Turkish Armed Forces), General Commandership of Gendarmerie, and MIT (National Intelligence Organization of Turkey) have not issued any comment on the lawsuit, up until this day. And considering the first hearing of the case has been conducted 7 months ago, they seem to be intent on maintaining this attitude.

A trafficking operation with its own military chain of command

What lies beneath the attempted trafficking is revealed by the truck driver Yalçın Kaya, in his testimonies at the police, and court hearings. The hired driver, who immediately got arrested after the police has confiscated the detonating cords hidden in the truck, claims that he agreed the gig, provided that the cargo to be transported to Urfa was ordinary construction material. Yet, when he personally met with his soon-to-be employer, Ahmet İzzet Sarıtaş, at a cottage house in Isparta, a partly rural town close to Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, Yalçın learnt that what previously mentioned as ‘construction material’ was indeed detonating cords. A former industrialist and current solar energy investor, according to his own words, Sarıtaş first introduced other three men sitting around the same table with him, “Gökhan [Nuri Gökhan Bozkır] works as a major at Spec-Ops, Mehmet [Mehmet Oktar] here is a major as well, at the infantry. And Tahir [Tahir Döner] is the manager of Ankara wholesale market hall.” Then he spilled the beans, “You’ll be carrying some explosive cables [Detonating cords] to Urfa. They’re to be received by ISIS. Do not worry though; the state backs us up. It’s for our martyrs.”

https://graphcommons.com/graphs/18320e4d-6e64-4882-88ee-8dc662389a12/eFor better display please visit GraphCommons: https://graphcommons.com/graphs/3769c3ec-09db-45b4-9dc2-b61ff924756e?auto=true

Turkey definitely has an intriguing history of its own, when it comes to conspiracy theories. Balyoz [Operation Sledgehammer], Ergenekon, and Feb 28 [Postmodern coup, 1997 Turkish Military Memorandum] trials, and all other public discussions speculating over conspiracies of some endogenous forces attempting to perform a coup d’état are to be included in this tradition that is infatuated with cabalist plots. Some also believe, during early 2000s, TSK composed an external defense and intelligence network for its own security. People who share that bias point out that a vast number of officials left TSK and General Commandership of Gendarmerie, especially during Feb 28 and Ergenekon eras, for being employed in civilian sectors (Municipalities, civil society organizations, etc.), within the scope of that ‘plan.’

One of the majors that assumed responsibility in the trafficking setup, Mehmet Oktar, had left his position in the Gendarmerie in 2000s, and became a civil servant at Ankara Metropolitan Municipality’s wholesale market hall, according to his co-workers. Fruit and vegetable middlemen, running their business at the wholesale market hall also told me that they found Oktar’s subsequent interest in Turkmen rebels fighting in Syria rather suspicious.

“In the last year, Oktar asked us to donate to Turkmen fighters’ cause. Well, in a place like wholesale market hall, every tradesman’s benevolence hangs on the administration’s lips, so you don’t want to go against those requests. Each time he asked for a donation for those fighters, shopkeepers gave away some cash, ranging from 500 to 1,000 TRY,” says a vegetable salesman. The wholesale market hall has 198 individual shops, which are operated by different middlemen; so Oktar might have raised 200,000 to 400,000 TRY ($69,000 to $138,000) single-handedly. And surely, there is no guarantee that money have really aided the controversial groups fighting in Syria, as shopkeepers tell that none were given any sort of receipt in return for the donation, “Traditionally that type of donations are done off-the-record,” one of them puts forward. So, this sum indeed, might have been used in the purchase of the detonating cords.

Arif İzzet Sarıtaş, the man who recruited driver-for-hire Yalçın Kaya, and introduced him to the other orchestrators Nuri Gökhan Bozkır and Mehmet Oktar, has other connections to arms and ammunitions trade, other than this operation of detonating cords trafficking. Turkish trade registry service reveals that, Arif İzzet Sarıtaş’ son, Ahmet Arif Sarıtaş owns a Bishkek-based arms trade company, which claims its target market is Kyrgyzstan.

Nevertheless, DNS Defence is not really into the inferior IED components business. According to its own export catalogues, the company sells pistols, assault rifles, machine guns (Machine guns to be mounted on vehicles and tanks are also in DNS Defence’s inventory – including a variation of ISIS favourite PKM or PSM type machine gun, a.k.a. Bixi), assassination rifles, mortars, grenade launchers, RPGs, towed air defense systems for land forces, anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles, every sort of projectiles and warheads, mines, and grenades. So basically, the company’s arsenal is capable of bringing Christmas early for any insurgent group. Additionally, Cumhuriyet Daily claims that another member of the criminal enterprise, Nuri Gökhan Bozkır, is among the owners of DNS Defence.

As curious intersections and connections are gathered together, the onion truck case looks more and more like a typical working day gone horribly wrong, rather than a one-shot trafficking. Trend Madencilik ve Patlayici [Trend Explosives], a Denizli-based company, is somehow connected to both Turkish firms, whose products have been used by ISIS during the siege of Kobane. Within the onion truck smuggling operation, Trend Explosives has been used as a proxy; the company bought 209 batches of detonating cords (209,000 meters) from Solar Explosives, whilst an additional 50 batches of detonating cords (50,000 meters) were acquired from Kapeks Patlayıcı [Kapeks Explosives], an Ankara based independent explosives producer that sells detonating cords produced by Sua Explosives of India. Without ever getting into the inventory of Trend Explosives, those batches were transferred to Yalçın Kaya’s truck during a roadside rendezvous close to Dinar, Afyon. Trend Explosives is owned by no other than one of the perpetrators of the whole operation, Mesut Doğanay. Doğanay, who became the sole owner of Trend Explosives on June 2014 (Doğanay acquired company shares for the first time on Jan 14 2013), personally escorted the transfer of detonating cords from trucks coming out of Solar Explosives (Together with detonating cords bought from Kapeks Explosives, shipped to Trend Explosives’ warehouse in Denizli on August 25) 2015), to Kaya’s ISIS-bound truck. Trend Explosives is also one of the official distributors of products of Nitromak Dyno Nobel, another company whose detonating cords have been found in Kobane.

Exploiting the loopholes: A policeman excelled in explosives

When the case of onion truck comes up while speaking to domestic explosive producers and mining engineers, each and every one of them state it is shocking to see such a huge leakage in this supposedly well-monitored system of production and distribution of explosives. Those who work at different levels of mining, construction, and explosives sectors constantly remark that the law in effect indeed provides a well conceived monitoring mechanism over misuses and possible attempts of explosives-running. When asked, the Chairman of UCTEA Chamber of Mining Engineers Ayhan Yüksel is able to recall only a single incident of violence related to misuse of explosives in a mine, during which a laid-off mining engineer strapped some dynamites around his waist and held his former supervisor hostage for an hour, only to abort the attempt after some policemen talked some sense into him. “In a mine, the probability of stealing vast or even small quantities of explosives is very slim, if not impossible. On a routine day, the blaster, the foreman, the storehouse supervisor, and perhaps the engineer in charge go over planned detonations, and oversee at the end of the shift whether the amount of explosives used correspond to the blasts realized, or not. Smuggling explosives out of a mine is only possible if the whole mine is a disguise for an organized act of trafficking, but that doesn’t make sense either; costs of such scheme would exceed the profits to be gained through sales of those explosives. Long story short, the cake’s not worth the candle,” Yuksel puts forward.

Another expert on production and sales of explosives, Müfit Erdil, board member of Kapeks Explosives, lays down the intricate licensing and monitoring framework within the sector. “Producers, importers, dealers, and end-users require different licenses for each and every transaction or operation. And Ministry of Interior is ever-watchful,” Erdil claims, nevertheless, the framework has its own loopholes – “Some parts of the transaction are based upon mutual trust though. For instance, before transporting explosives from our factory to a dealer obliges us to disclose the amount and type of the explosives, the transportation route, the final destination, and so forth to the authorities. Our truck, the driver, and the qualified technical escort need to fulfill all requirements as well. Once the cargo reaches the desired destination, the driver should notify the local police or gendarmerie of their arrival. The final thing to do is filing an official statement indicating the arrival of explosives to the warehouse. But in some cases, local police or gendarmerie does not take the trouble of personally escorting and monitoring that phase. They yet, sign the documents, without actually seeing the transfer of explosives from the truck to the warehouse; based on the mutual trust they have with the dealers. Unless being aware of such loopholes, owner of Trend Explosives could have dared to smuggle explosives in such volume.” Mesut Doğanay, owner of Trend Explosives, was in fact quite aware of those loopholes, by his profession. Doğanay had left behind a career at Denizli Police Department to enter into the explosives business, following his departure from Firearms and Explosives Branch Office. Some would say Doğanay was the natural candidate for running such a smuggling operation, due to knowledge and experience gained over years of his work at the force. Erdil also acknowledges the actual amount of detonating cords sold to Trend Explosives was 200,000 meters, but only a quarter of that sum had been seized when the truck was halted at Akçakale on Sep 8 2015.

“We have no idea of the whereabouts of the remaining 150,000 meters of detonating cords, neither has the chief public prosecutor’s office of Dazkiri. Kapeks Explosives had already issued a confiscation order over Trend Explosives’ assets vis-à-vis standing debts, including the dues arisen by the previous sales. However, after receiving the warrant of seizure by Sanliurfa chief public prosecutor’s office, chief public prosecutor’s office of Dazkiri –which is located very close to Trend Explosives’ warehouse– had already issued a search warrant, and failed to seize any detonating cords. So, at least 150,000 meters of detonating cords are officially missing.

Twin brothers Doğan Güneş and Gökhan Güneş, who were assigned to escort the onion truck with their own vehicle during the shipment, later claimed that they got involved in the explosives-running scheme through –yet another military personnel in the smuggling operation– Lieutenant Ahmet Yasin Güneş, a man they became coincidentally acquainted with in Ankara. In one occasion, Doğan Güneş claimed on his written statement given to the court, together with Lieutenant Güneş, he went to a luxurious villa next to Spec-Ops HQ in Ankara, and later while they were there, two fellows brought 2 Stinger missiles down from the roof of that villa. According to Doğan Güneş, Lieutenant Güneş confessed to him, acknowledging that he was doing counter-terror work behalf of the National Intelligence Organization of Turkey (Official records show that Lieutenant Güneş works for General Commandership of Gendarmerie). Additionally, as reported by Cumhuriyet Daily’s Canan Coşkun, Lieutenant Ahmet Yasin Güneş is none other than one of the anonymous witnesses of one of Turkey’s most high profile lawsuits in recent years, the ‘MIT trucks’ case, another gun-running operation bound to Salafi jihadists fighting in Syria. This particular case is not to be mistaken with the internationally known espionage case against journalists Erdem Gül and Can Dündar though; Lieutenant Güneş is claimed to be an anonymous witness in the case which military personnel, including generals, are accused of attempting to stage a coup d’état.

IED is the weapon of choice

Distressed by explosives sector’s contemporary coupling with Salafi jihadists due to recent developments, the owner of an explosives company, who should be left unnamed, tells me that police in Turkey has finally started to take the issue more seriously. “Now that those supply routes came into light, after April 2016, police began conducting meetings with explosives producers and sellers in each province, reminding them of their obligations, and other rules and regulations. But it’s too little too late…” Other sources claim that the government commanded police to take necessary steps as late as April this year, ordering local security forces to check whether the records of the companies actually comply with their stocks in the inventories, or not. Nevertheless, the timing indicates Ankara has a solid threat perception vis-à-vis TAK, or any other Kurdish insurgent group, rather than ISIS or Jabhat al-Nusra. Even if Ankara’s intelligence sources had been dried up back then, the government became aware of Maxam’s detonating cords on June 10 2015, then learnt about the onion truck on Sep 8 2015, and finally saw Turkish companies associated with ISIS’s IEDs upon the release of CAR’s report, but ruling AKP decided to act against trafficking of an IED component, detonating cords, only after TAK’s suicide attacks targeted TSK and police posts in the capital on March 2016.

Current affairs in Iraq prove that IEDs are useful during positional defense, or tactical retreats as well. Knowing the potential risks involved, US-led coalition aircraft bombed an IED laboratory belonging to ISIS, almost a month before Iraqi forces’ land offensive to Fallujah, last ISIS-held major city in Iraq, had begun. Following the troops’ entry into the town, it wasn’t surprising to find out that the Fallujah’s own population was under threat of encountering IEDs that have been concealed to undisclosed locations by the Islamic State, in case they attempt to flee the city. Indeed, IEDs are more worrying for Iraqi commanders, compared to direct contact with battle-weary ISIS ranks. Middle East and Iraq observer Haider Sumeri quotes an officer of Iraq’s Rapid Response Division taking part in clashes in Fallujah, “Every meter there’s an IED, every 100-200 meters there’s a car bomb…” officer says.

ISIS’s preference for IEDs goes for attacks perpetrated outside the Islamic State too. In a speech on September 2014, ISIS spokesperson Abu Muhammad al-Adnani advised supporters and sympathizers to organize as many attacks as possible everywhere, “Do not ask for anyone’s advice and do not seek anyone’s verdict . . . If you are not able to find an IED or a bullet, then . . . smash his head with a rock, or slaughter him with a knife, or run him over with your car, or throw him down from a high place, or choke him, or poison him. Do not lack,” he stated.

It is not long now before; while the pressure has mounted for a full-scale Coalition ground offensive to ISIS heartland Raqqa province, al-Adnani has reiterated this horrendous proclamation. In his speech released by Al Hayat Media on May 21, al-Adnani claimed that hard measures against the Dawla is short sighted and futile, “…would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqa or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not!” And his advice to followers of the Islamic State was point blank, “O muwahhiddin [Believers of Tawhid]! If the tawaghit [Also known as taghut, in this context, it refers to an administration that neither draws its authority from divinity, nor rules in accordance with Salafi principles] have shut the door of Hijrah [Leaving for holy land] in your faces, then open the door of jihad in theirs. Make your deed a source of their regret. Truly, the smallest act you do in their lands is more beloved to us than the biggest act done here; it is more effective for us and more harmful to them. If one of you wishes and strives to reach the lands of the Islamic State, then each of us wishes to be in your place to make examples of the crusaders, day and night, scaring them and terrorizing them, until every neighbor fears his neighbor. If one of you is unable, then do not make light of throwing a stone at a crusader in his land, and do not underestimate any deed, as its consequences are great for the mujahidin and its effect is noxious to the disbelievers” he puts forward. If al-Adnani’s words are taken seriously by the Salafi sympathizers living in Europe, US, Turkey, and those countries who joined their forces with anti-ISIS coalition, we may yet witness more individual or organized attacks in the West, as the Dawla keep increasing its expertise on IEDs, to a certain degree thanks to supply routes established over Turkey.

Footnotes

[1] Conflict Armament Research, “Tracing the supply of components used in Islamic State IEDs”, p.21, GPS coordinates detonating cord found at: 36.892334, 38.352662

[2] Traceability measures of explosives should be mentioned as well.

[3] Several Turkish explosives producers that I had conversations with tell that none of the explosives companies in Turkey produce detonating cords domestically, due to competitive advantages enjoyed by international producers. According to them, costs of producing detonating cords offset the potential profits; therefore while companies produce ANFO and most detonators in their inventory, they choose to import detonating cords.

***

Explanations and photo credits to the images and graphs

Image-1: Aftermath of Oct 10 2015 Ankara suicide attack, realized through suicide-vest borne IEDs. Photo credit: Defne Karadeniz/Getty Images

Table-1: Statistics derived from ISIS annual reports. Retrieved from ISW Report

Image-2: Maxam Anadolu’s invoice, regarding sales of detonating cords to ASR Trading Company

Map-1: Proposed route of detonating cords shipment through Syria. Credit: Doğu Eroğlu

Image-3: The letter in which Lebanese officials disclose information on Maybel Co. Sarl, upon CAR’s request. Retrieved from CAR Report

Image-4: Maybel’s detonating cords, as documented by CAR. Retrieved from: CAR Report

Image-5:Some of the IEDs documented by CAR researchers. Retrieved from CAR Report.

Image-6: Detonating cords sold by Nitromak Dyno Nobel and Solar Explosives (Formerly known as İlci Patlayıcı), as documented by CAR. Retrieved from CAR Report.

Image-7: Retrieved from Solar Industries’ 2014-15 Annual Report.

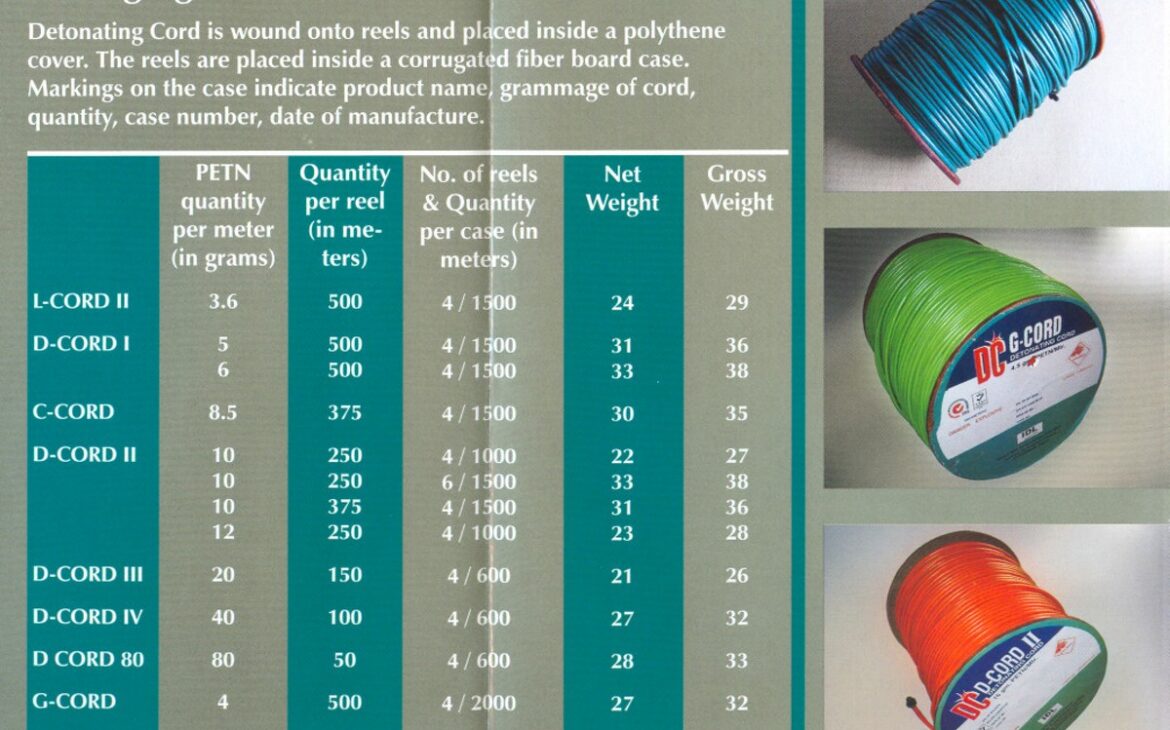

Image-8: Retrieved from IDL Explosives printed product catalogue.

Map-2: The movement of detonating cords, within ‘the onion truck case’ Credit: Doğu Eroğlu

Image-9: Ankara Metropolitan Municipality’s Wholesale Market Hall

Image-10: DNS Defence’s Turkey records show that the company is owned, and founded by Ahmet Arif Sarıtaş. Source: Turkey Trade Registry Gazette, issued on Dec 28 2015.

Image-11: The official family record, showing that Ahmet Arif Sarıtaş is indeed Arif İzzet Sarıtaş’ son.

Image-12-13-14: Retrieved from DNS Defence Export Catalogue.

Image-15: Permit received from local police regarding the shipment of detonating cords sold by Kapeks Explosives to Trend Explosives. Photo credit: Doğu Eroğlu

Graph Commons graph-1: Supply chain of detonating cords – Credit: Doğu Eroğlu – https://graphcommons.com/graphs/57bc335a-6a4a-4554-b0c1-c33e061b2b73

Graph Commons graph-2: Onion trucks – Credit: Doğu Eroğlu – https://graphcommons.com/graphs/3769c3ec-09db-45b4-9dc2-b61ff924756e

***

Different versions of this article have appeared in Turkish, on Turkish Daily Birgun.

– http://www.birgun.net/haber-detay/cihatcilar-icin-tedarik-zinciri-107494.html

http://baskaldiraninsan.com/2016/03/28/turkiye-isid-ve-el-nusranin-patlayici-malzemeleri-icin-nasil-ithalat-ihracat-merkezi-oldu/

– http://www.birgun.net/haber-detay/isid-e-infilakli-fitil-kaciran-sebekenin-organizatoru-eski-polis-cikti-117965.html

– http://www.birgun.net/haber-detay/patlayicilara-onlem-almak-emniyet-in-aklina-simdi-geldi-117491.html

– http://www.birgun.net/haber-detay/sogan-tir-indaki-fitillerin-parasi-toptanci-hali-nden-118223.html